A rare case report of Coats’ disease

Madan Kulkarni V.1*, Madhukar Sabnis M.2, Kailashbhai Kalaria H.3, Vivek Agarwal H.4

DOI: https://doi.org/10.17511/jooo.2020.i07.05

1* Vedesh Madan Kulkarni, Resident, Department of Ophthalmology, Dr. D Y Patil Medical College, Hospital & Research Institute, Kolhapur, Maharashtra, India.

2 Milind Madhukar Sabnis, Professor and Head of Department, Department of Ophthalmology, Dr. D Y Patil Medical College, Hospital & Research Institute, Kolhapur, Maharashtra, India.

3 Hardik Kailashbhai Kalaria, Resident, Department of Ophthalmology, Dr. D Y Patil Medical College, Hospital & Research Institute, Kolhapur, Maharashtra, India.

4 Himali Vivek Agarwal, Resident, Department of Ophthalmology, Dr. D Y Patil Medical College, Hospital & Research Institute, Kolhapur, Maharashtra, India.

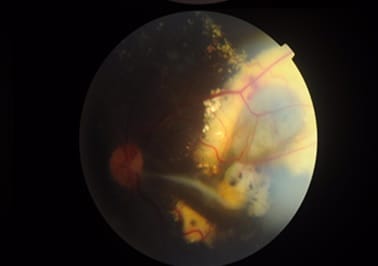

Coats’ disease was first described by George Coats, as a unilateral retinal vascular abnormality. Coats’ disease is a nonhereditary, idiopathic disease presenting with vascular telangiectasia with intraretinal and subretinal exudation with no racial preponderance and systemic associations. Coats’ disease presents with a wide ambit of clinical features- vision loss, strabismus, leukocoria, or nystagmus. The three classical features that are pathognomonic of Coats’ are exudative retinal detachment, telangiectatic vessels, and peripheral retinal ischemia. The modalities for treatment of Coats disease that can be used are laser photocoagulation, anti-VEGF agents, or a combination of both and cryotherapy. This article describes a case report of a 10-year-old male child with complaints of painless loss of vision, his ophthalmological evaluation, and the treatment is undertaken.

Keywords: Coats disease, Exudation, Telangiectasia

| Corresponding Author | How to Cite this Article | To Browse |

|---|---|---|

| , Resident, Department of Ophthalmology, Dr. D Y Patil Medical College, Hospital & Research Institute, Kolhapur, Maharashtra, India. Email: |

Kulkarni VM, Sabnis MM, Kalaria HK, Agarwal HV. A rare case report of Coats’ disease. Trop J Ophthalmol Otolaryngol. 2020;5(7):194-199. Available From https://opthalmology.medresearch.in/index.php/jooo/article/view/166 |

©

©